Studying in another country is an act of courage in every sense. Of course, it is a decision that can lead to new academic and work opportunities, but it can also raise many questions about identity. It is a brave bet, both economically and emotionally, which inevitably places the student in a bardo position (an intermediate or transitional state between here and there). Even in a world as globalized as ours, leaving Latin America to study in another continent is not the rule, but rather the exception. According to official data, about 200 students of Latin American origin are enrolled at Uni Bremen, which is approximately 7% of all international students and 1% of all students on campus. Although it is not a large number, I wanted to get closer to those who make up the percentage and hear first-hand what only they can tell us. For the ancient Celts, a bard was the person in charge of transmitting the stories of his people before different audiences: messengers of experiences and oral ambassadors. I asked five modern bards, from different Latin American countries, to tell us their stories.

The main objective was to understand what it feels like to be a student of Latino origin in another country. Developing a “typical” profile of the Latino student is complicated; however, there is a fairly marked group identity. And as a group, the way we live and perceive this academic stage is sometimes similar. Álvaro (from Mexico), Gabriela (from Chile), Flavia (from Argentina), Juan Camilo (from Colombia), and Rolando (from Costa Rica) are students in different situations though: they do not coincide in age, field, grade of study, or command of the German language.

Álvaro started the Master in Control, Microsystems, and Microelectronics (in English) in 2021. His decision to study in Bremen was guided by the academic offer (the study program that most interested him). Gabriela pursues her Ph.D. in Romanistik since 2022 (in Spanish). Her decision was born from a specific recommendation from her tutor in Chile. Flavia studies the Master in Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering at Hochschule Bremen since 2022 (in English) and takes German courses at Uni Bremen. She decided to study in Bremen because the program of her dreams was available here, in a city she felt attracted to, and taught fully in English. Juan Camilo pursues a Ph.D. in Isotopic Geochemistry since 2020 (officially in English, but some discussions take place in German or even Portuguese). The opportunity to come to Bremen was somewhat unexpected for him. He previously studied in Brazil and Colombia. Rolando has been studying Hispanism and Religious Studies since 2019. He chose the Uni of Bremen as the second-best alternative to the University of Hamburg.

What do they like most about studying in Bremen?

We agreed that Bremen is an ideal city for international students. Rolando mentions that the city has a perfect size and relatively affordable living costs. “It’s not a big city, but it has everything regarding entertainment, sports, affordable housing, and a wide variety of study programs. Also, it’s well connected by public transportation and biking, while the semester ticket covers all the way to Hamburg, in case every now and then you need to feel big-city vibes again”, commented Flavia.

Regarding university services, some of their favorite characteristics are the student facilities and infrastructure, the sports offer, the Mensa, the fact that the institutes are so close, the friendly atmosphere, the flexibility, and the opportunity to organize the time of study independently, which makes it easier to integrate other activities into the day. For Gabriela, a pleasant surprise was finding a mural painted by Chilean artists during the dictatorship period. I recommend looking for it.

Original: Chilean group „Brigada Luis Corvalán” and Bremen art students / Reconstruction: Jub Mönster, June 1976 / June 2014

Challenges and opportunities for improvement

The biggest challenges tend to be bureaucratic: the entry requirements, the application processes that are sometimes not well understood, and the paperwork to request resources from the Uni. A good idea would be to introduce step-by-step explanatory documents in English or Spanish for programs especially aimed at Latin American students and thus facilitate information channels. Likewise, Rolando pointed out that the biggest barrier for Latin Americans who want to study in Bremen at the undergraduate level is the requirement of English and German at a fairly high level.

On the other hand, in faculties where programs are offered entirely in English, there is often a noticeable disconnection between international and German students. Sometimes the structure favors the formation of bubbles that do not fully integrate. In this sense, it is important to have other courses or spaces that international students can share with local students outside of their programs.

Differences

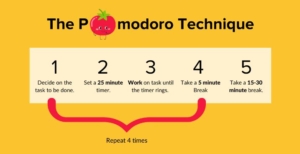

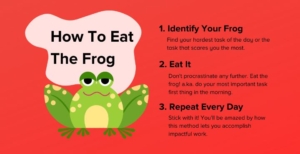

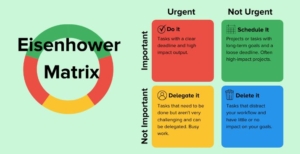

As discussed with Álvaro, one of the biggest differences is the absence of mandatory handing in of papers or projects throughout the semester in Bremen. This might be problematic for those who come from the Mexican academic context, much more used to constant delivery and assessment. In German universities, performance is usually graded with a single test at the end of the course, which affects the learning approach. The same thing happens with the obligation to attend classes (which is very common in Mexico); this absence in Bremen also reduces classmate interactions. A Mexican student in Germany is faced with a lot of (apparently) free time, which is an opportunity to practice proper time management.

Regarding self-management, sometimes life can be very chaotic in Latin America due to social and political factors that are outside of the student’s control. This might affect routines and, therefore, the quality of studies. In that sense, Bremen is more predictable, and the ease of life and studies depends more on personal choices. With Flavia and Juan Camilo, I remembered that many times the quality of education in Latin America depends on the public or private nature of the institution. This is problematic when laboratory experience is needed. Bremen has the advantage of offering bigger budgets, which can provide better equipment and other kinds of resources. Some differences in terms of research support are more notorious at the postgraduate level. Paying for analysis, working a lot in the laboratory, proposing new ideas for studies, traveling and presenting papers at congresses might be a bit more complicated in Colombia, but in universities like São Paulo or Bremen it’s not a big problem. However, with this increased availability of resources, there is also an increase in bureaucracy.

One of my interviewees.

Another surprising difference is the shorter time a Ph.D. is expected to last in Bremen: 3 years compared to 4-5 in most of Latin America. According to Gabriela, one main difference is that doctoral programs in our countries are structured (with courses); while here one can take a Ph.D. only focused on research, and work independently under the supervision of a tutor. Another difference is the costs. In Chile education is quite expensive, whereas here students have greater benefits. Finally, a difference that Rolando identifies between studying at Uni Bremen and in Costa Rica is the relationship between teachers and students. In his opinion, interactions there feel closer, while still respectful.

Summing up, from my interviews I conclude that, although there are clear economic differences between some public Latin American universities and Uni Bremen, the academic level is absolutely comparable. I also found out that my colleagues don’t miss studying in their home countries and that they would all recommend studying at our beloved Uni Bremen. Everyone feels integrated; however, they sometimes miss the ease with which they could make friends in their countries. Some plan their arrival in Germany years in advance, but others also seize a more sudden opportunity. Some have plans to continue studying or to apply for jobs in international environments; it seems to me that none contemplates the possibility of returning to their country of origin as a first option. The recognition of German universities is a great academic advantage: a German degree opens more doors abroad. Finally, the overall value of their study abroad experience is very positive, both in academic and personal terms. And I agree.

Are you interested in learning about other international student groups? Do you have plans to study in another country? Let me know in the comments. Until next time!

In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Green House Center versucht die Uni Bremen jährlich bis zu 2,8 Millionen kWh an Energie und bis zu 3,2 Millionen kWh an Kältebedarf einzusparen. Das Green House Center ist übrigens das Rechenzentrum an der Uni Bremen, wo jedes Vorlesungsvideo, gespeicherte Dateien und Daten wiederzufinden sind.

In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Green House Center versucht die Uni Bremen jährlich bis zu 2,8 Millionen kWh an Energie und bis zu 3,2 Millionen kWh an Kältebedarf einzusparen. Das Green House Center ist übrigens das Rechenzentrum an der Uni Bremen, wo jedes Vorlesungsvideo, gespeicherte Dateien und Daten wiederzufinden sind.

Der am meiste genannte Punkt, der den bisherigen Studis beim Unistart geholfen hat, ist der der Kontakte knüpfen. Sowohl in der O-Woche, als auch in den sozialen Netzwerken, hast Du als Erste die Möglichkeit neue Leute kennenzulernen. Die meisten Fachbereiche bieten zudem verschiedene Veranstaltungen und Events an, wo du dich vernetzen kannst. Viel erfahrene Studis berichten, dass sie ihre zukünftigen Kommilitonen in der O-Woche ihres Studiums kennengelernt haben und mit denen auch die meiste Zeit im Studium verbracht haben. Zudem sind viele Online-Gruppen via WhatsApp bspw. hilfreich um sich bei den ersten Fragen und Unsicherheiten auszutauschen. Daher: traue dich, schreibe Leute an, gehe auf sie zu und lerne deinen Kommilitonen kennen. Die meisten fühlen sich am Anfang vermutlich genauso überfordert wie du, von daher tauscht euch aus und erkundet das Uni Leben zusammen.

Der am meiste genannte Punkt, der den bisherigen Studis beim Unistart geholfen hat, ist der der Kontakte knüpfen. Sowohl in der O-Woche, als auch in den sozialen Netzwerken, hast Du als Erste die Möglichkeit neue Leute kennenzulernen. Die meisten Fachbereiche bieten zudem verschiedene Veranstaltungen und Events an, wo du dich vernetzen kannst. Viel erfahrene Studis berichten, dass sie ihre zukünftigen Kommilitonen in der O-Woche ihres Studiums kennengelernt haben und mit denen auch die meiste Zeit im Studium verbracht haben. Zudem sind viele Online-Gruppen via WhatsApp bspw. hilfreich um sich bei den ersten Fragen und Unsicherheiten auszutauschen. Daher: traue dich, schreibe Leute an, gehe auf sie zu und lerne deinen Kommilitonen kennen. Die meisten fühlen sich am Anfang vermutlich genauso überfordert wie du, von daher tauscht euch aus und erkundet das Uni Leben zusammen. Viele von Euch Erstis sind für ihr neues Studium nach Bremen gezogen. Raus aus der Heimat, raus aus dem vorigen zu Hause und der gewohnten Umgebung. Das kann gerade am Anfang ganz schön viel sein und vielleicht kennst auch Du den Moment, wo man sich einsam und nicht wirklich zu Hause fühlt. Den wichtigsten Tipp den wir dir mitgeben können, ist deine neue Heimat auch zu deinem neuen zu Hause zu machen. Gehe raus, erkunde Bremen und sammle in der neuen Stadt zusammen mit deinen Freunden neue Erfahrungen. Um die Stadt Bremen und all seine Geheimecken am besten zu erkunden, können wir Dir den Instagram Kanal

Viele von Euch Erstis sind für ihr neues Studium nach Bremen gezogen. Raus aus der Heimat, raus aus dem vorigen zu Hause und der gewohnten Umgebung. Das kann gerade am Anfang ganz schön viel sein und vielleicht kennst auch Du den Moment, wo man sich einsam und nicht wirklich zu Hause fühlt. Den wichtigsten Tipp den wir dir mitgeben können, ist deine neue Heimat auch zu deinem neuen zu Hause zu machen. Gehe raus, erkunde Bremen und sammle in der neuen Stadt zusammen mit deinen Freunden neue Erfahrungen. Um die Stadt Bremen und all seine Geheimecken am besten zu erkunden, können wir Dir den Instagram Kanal  Die Universität Bremen bietet allen Studierenden ein umfangreiches Hochschulsport-Programm an. Von klassischen Sportarten wie Volleyball, Schwimmen, Bouldern oder Fussball, findest du in dem Kursprogramm auch ausgefallenere Aktivitäten. Darunter zählen zum Beispiel Burlesque, Drachenfliegen in Frankreich, Hula Hoop oder Röhnrad an. Der Vorteil von Hochschulsport ist, dass du neben deinem Studium ausreichend Bewegung hast und zugleich neue Leute kennenlernen kannst. Und das ganze für ganz niedrige Preise, die sich jeder Studi leisten kann. Das Kursprogramm des Hochschulsports an der Uni Bremen findest du hier:

Die Universität Bremen bietet allen Studierenden ein umfangreiches Hochschulsport-Programm an. Von klassischen Sportarten wie Volleyball, Schwimmen, Bouldern oder Fussball, findest du in dem Kursprogramm auch ausgefallenere Aktivitäten. Darunter zählen zum Beispiel Burlesque, Drachenfliegen in Frankreich, Hula Hoop oder Röhnrad an. Der Vorteil von Hochschulsport ist, dass du neben deinem Studium ausreichend Bewegung hast und zugleich neue Leute kennenlernen kannst. Und das ganze für ganz niedrige Preise, die sich jeder Studi leisten kann. Das Kursprogramm des Hochschulsports an der Uni Bremen findest du hier:  Die Uni Bremen ist groß und hat mehrere Standorte, an denen deine Vorlesung stattfinden kann. Selbst erfahrene Studis berichten, dass sie sich immer noch regelmäßig im GW2 verlaufen und ihren Vorlesungsraum einfach nicht finden.

Die Uni Bremen ist groß und hat mehrere Standorte, an denen deine Vorlesung stattfinden kann. Selbst erfahrene Studis berichten, dass sie sich immer noch regelmäßig im GW2 verlaufen und ihren Vorlesungsraum einfach nicht finden. Viele weitere hilfreiche Tipps für deinen Start an der Uni Bremen bietet das

Viele weitere hilfreiche Tipps für deinen Start an der Uni Bremen bietet das